(Vivienne Liu, Cornell Engineering PhD Candidate and TA Trainer Consultant, contributed strongly to this reflection by bringing the paper to our summer development workshops and sharing her ideas for classroom application)

‘Engagement’ is a term used a lot these days in discussions about successful education experiences. Learning occurs in a complex matrix which makes it sometimes challenging to understand the outcomes of our practice. It doesn’t help that we toss around terms of the trade like engagement as if everyone – including ourselves as educators – understands them, particularly out of context!!

‘Engagement’ is a term used a lot these days in discussions about successful education experiences. Learning occurs in a complex matrix which makes it sometimes challenging to understand the outcomes of our practice. It doesn’t help that we toss around terms of the trade like engagement as if everyone – including ourselves as educators – understands them, particularly out of context!!

This post about individual student emotional and cognitive engagement, is the first in a series of three. This is the logical start to unraveling some of the mechanisms influencing what happens in classrooms – virtual or face-to-face.

Stay tuned for more about how these two aspects of engagement interact with group dynamics to create the more familiar ‘behavioral engagement’ (Part 2) and, ultimately, trouble shooting some of the complexity that occurs in peer-to-peer and interactions in this complex ecosystem (Part 3).

The Glossary of Education Reform defines engagement this way:

“student engagement refers to the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, optimism, and passion that students show when they are learning or being taught, which extends to the level of motivation they have to learn and progress in their education. Generally speaking, the concept of “student engagement” is predicated on the belief that learning improves when students are inquisitive, interested, or inspired, and that learning tends to suffer when students are bored, dispassionate, disaffected, or otherwise “disengaged.””

While the term is so broad as to be considered not useful by some researchers, Ashwin and McVitty (2015) maintain that it has many ‘faces’ and is extremely valuable once we, 1) define the context in which engagement is occurring and 2) articulate the goal of creating engagement. For our purposes, lets limit our discussion to engagement by students for the goal of improving learning outcomes in online and face to face classes.

Many who have spent years teaching in the face-to-face environment have an intuition that teaching online will not illicit the same learning outcomes that we believe occur in in-person classes. In this time of emergency remote teaching for so many, understanding something about creating engagement in general and specifically in the online learning environment is important.

Engagement is influenced by factors both within and outside of our control as learning facilitators. Knowing a little bit more about what results in variation in student engagement will, at least, help us better understand why there can be so much variability in learning outcomes and, at best, suggest some of the strongest empirical connections to learning outcomes so that we might gradually apply them (or, if they are negative, avoid them!). The summary of results from a paper shared here examines the influence of course delivery mode, and does a nice job of incorporating many of the potentially explanatory factors related to engagement.

Engagement is influenced by factors both within and outside of our control as learning facilitators. Knowing a little bit more about what results in variation in student engagement will, at least, help us better understand why there can be so much variability in learning outcomes and, at best, suggest some of the strongest empirical connections to learning outcomes so that we might gradually apply them (or, if they are negative, avoid them!). The summary of results from a paper shared here examines the influence of course delivery mode, and does a nice job of incorporating many of the potentially explanatory factors related to engagement.

Manwaring et al, 2017 conducted a multivariate analysis in face-to-face and hybrid model courses to try to understand the factors that influenced the two major components of engagement: cognitive and emotional. Emotional engagement (EE), is the way a student feels about aspects of the learning process (the affect), and cognitive engagement (CE), is the amount of effort a learner expends on the task at hand. One study does not the truth make, particularly one with such a small sample size! But this study trades-off large sample size and examining a few controlled independent variables and indicators, for a detailed look at just about every variable but the kitchen sink! They survey a smallish group of students (68), but ask for their responses for a large number of individual class meetings the students attended within a semester. Many of the outcomes are corroborated by other research.

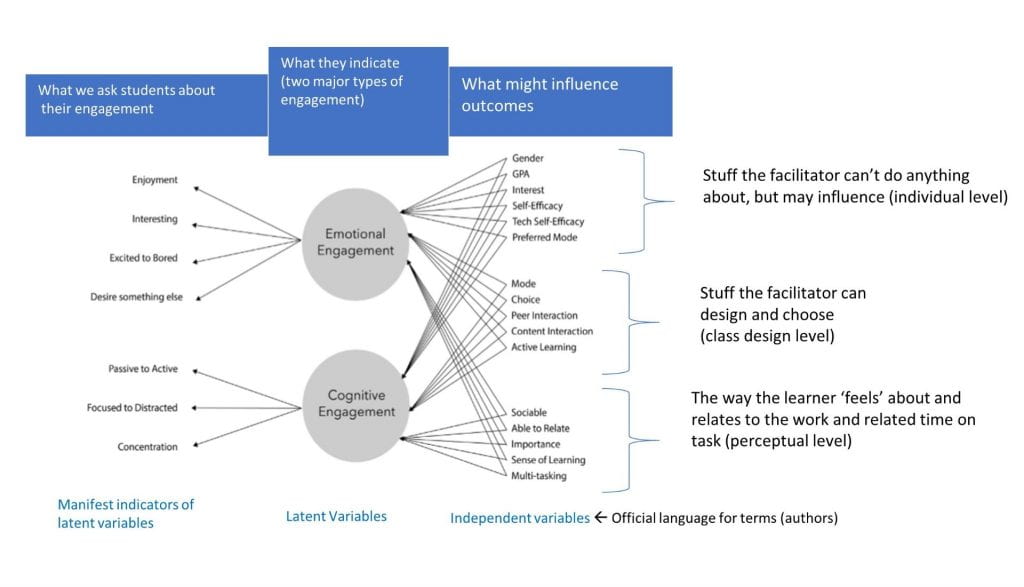

Figure 1. Adapted from Manwaring et al 2017. The model the authors used to survey student engagement.

In a nutshell this figure, adapted from the study, illustrates the complexity of the learning environment and names many possible components of ‘engagement’. Another important point is that level of student engagement is a result of factors specific to individuals (individual level), as well as those influenced by the context (class design and perceptual levels). Appendix 1 in the publication includes the entire survey instrument, but as an illustration some of the questions on the 5-pt Likert-scale instrument include: How well were you concentrating? Did you feel good about yourself? Were you learning anything or getting better at something? Did you have some choice in picking this activity? How hard have you worked to keep up with this class? How much time have you spent on this class? What else were you doing?

The analysis for this study used Hierarchical Structural Equation Modeling (HSEM). Here is a link to a fairly short but useful video that explains the way SEM works.

Using the outcomes of this paper, the remainder of this post will be spent creating a paired down, tangible picture of:

- Which factors appear to create or discourage the two aspects of student engagement?

- Which type of engagement seems more complicated to achieve?

- Where is the overlap in factors that seem important for both types of engagement?

and suggesting practical strategies we can apply in our online, face-to-face, and hybrid model courses using this information. Having said that, in the interest of transparency, the table below is the main outcome of the analysis in all of its detail for those who want more information and to draw their own conclusions.

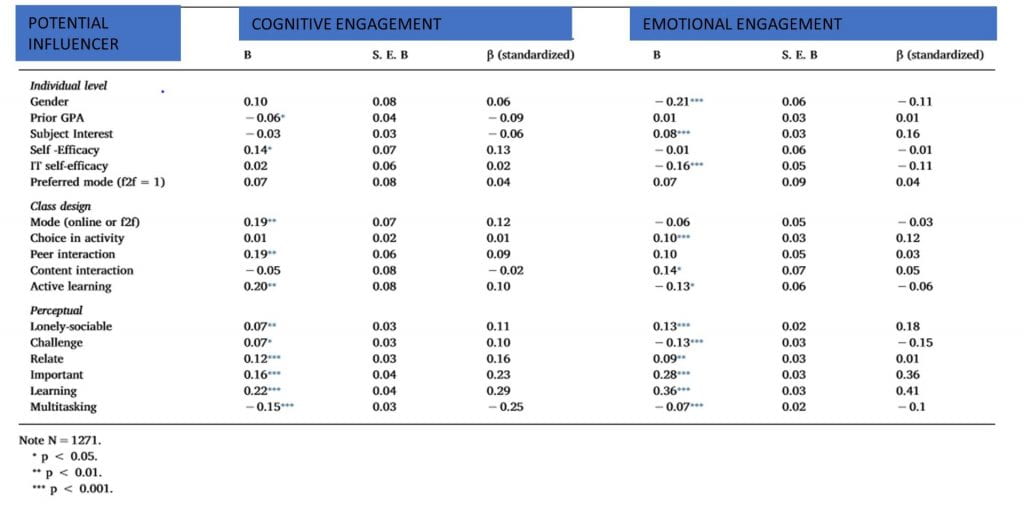

Figure 2. Table 6 from Manwaring et al, 2017. Presented for full disclosure of all the interesting results including some we won’t discuss in this blog. This is for those who love data! For the Gender variable 0 = male, 1 = female.

‘Big picture’ outcomes jump out of the complex table above in answer to our questions. Note that the statistical strength of the relationship of each individual variable for ‘cognitive engagement’ on the left and ‘emotional engagement’ on the right are represented using asterisks (*) in the columns labelled ‘B’. More asterisks = stronger relationships. Of the 17 total factors represented in the table, asterisks appear next to 12 variables for emotional engagement, and 11 for cognitive engagement. The larger difference comes in the strength of the relationships. Emotional engagement is highly significantly associated (***) with 9 of the listed factors, while cognitive engagement has only 4 variables that show this level of significance. Finally, the most significant relationships with respect to emotional engagement are quite evenly distributed across individual, class design and perceptual categories, while cognitive engagement is more a function of factors that are associated with class design and student perception. The bulk of strong influencers appear to be in the perceptual category for both emotional and cognitive engagement. With respect to the role of mode of learning (online or face-to-face), this study does suggest that cognitive engagement is enhanced in the face-to-face environment, while ‘mode’ has no effect on emotional engagement.

In summary:

- Both emotional and cognitive engagement are influenced by many factors – they are complex!

- Emotional engagement may be more challenging to achieve because there are more individual factors with which it is associated.

- Both types of engagement are most strongly affected by the aspects of student perception

- The mode in which learning is happening (online or face-to-face) appears to be less associated with how engaged students are than some of the other variables in the study, and is only significant for cognitive engagement

It appears that getting and keeping individual college students feeling interested in a class and motivated to learn is more complex, and less under the control of the teacher, than is getting students to do the work of thinking and learning. In this study, face-to-face learning was more cognitively engaging than online learning, however, there are many variables that we can work with to combat any loss that occurs either online or face-to-face.

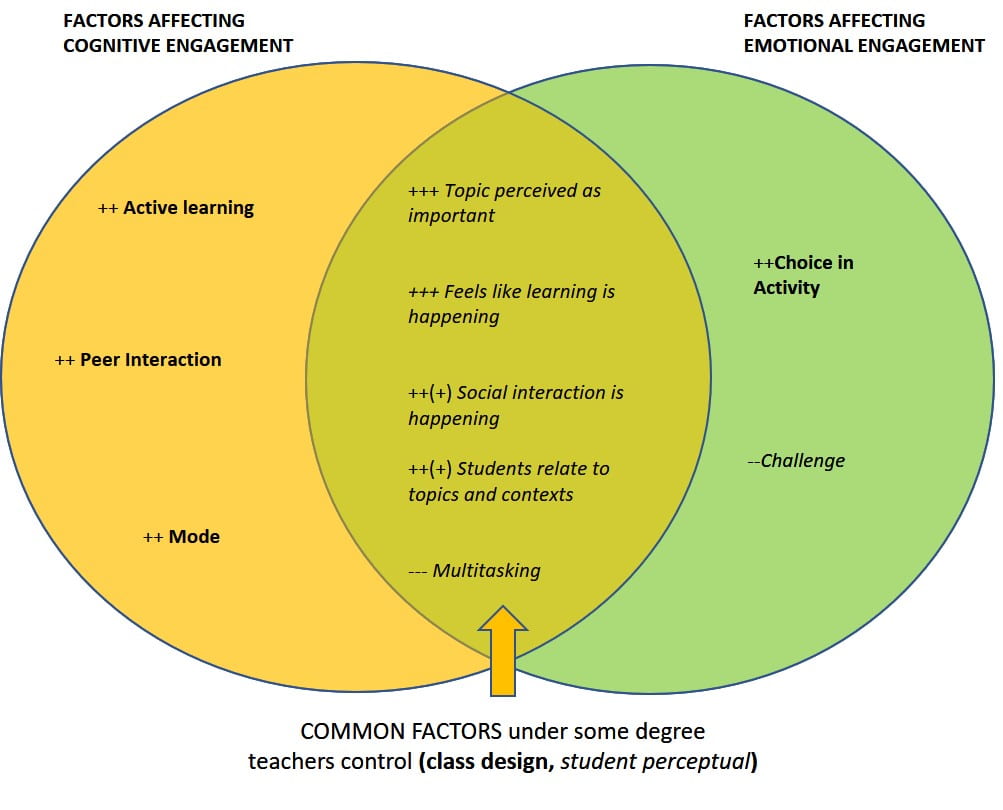

Clearly these two aspects of engagement interact and there is overlap in variables that influence both forms of engagement, particularly in the area of perception (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The overlap in class design and perceptual factors that influence both emotional and cognitive engagement. Intentionally excluded are individual aspects associated with students because they are more difficult to control. Note: Class design variables are bold and perceptual factors are Italicized (this figure displays outcomes from Table 6 from Manwaring et al (2017) as a Venn diagram to illustrate the most fruitful opportunities to apply in practice to increase ind. student engagment.

Linking research outcomes to practice: What practical strategies can we apply to increase individual student engagement in our online, and face-to-face courses.

The low hanging fruit for practical applications are those factors that exist in the overlap between cognitive and emotional engagement. Let’s start with the one factor strongly negatively associated with both forms of engagement:

Multitasking

A challenge of online teaching is that it’s hard, maybe impossible, to know what students are doing on the other side of the screen. In both environments we can apply these practices:

-

At the start of the semester and in each class share your expectation for an atmosphere of mutual respect. Initially sharing yours and asking students to share their ideas of what this means and developing a list of agreed upon behaviors can act as a verbal contract. Refer to the contract at the start of each class when you ask them to please be ‘really present’ for your time together.

-

Studies have shown that sharing research information about why you use certain teaching practices (providing an evidence-based rationale such as Manwaring et al, (2017)) will help with buy-in from students, particularly when you show that it influences their performance and ultimately their grade.

-

Requiring/encouraging/providing regular expectation that students participate in simple (polling, commenting in the chat, annotating on the shared screen) or more complex (think-pair-share , group work, worksheets associated with presented materials) active learning during class (online or face-to-face) will reduce time that students can be multitasking

Ways that one might try to encourage both emotional and cognitive engagement include activities that:

make the materials seem important, help students realize that learning is happening, are more social in nature, and seem related to their lives and situations

-

Provide real-world examples in lecture and/or in homework to show the importance of what they’ve learned and create examples students relate to.

-

Ask students to provide examples of applications for what they learned in the class.

-

Require brief ‘reflection pieces’ (written or audio recordings) either during or at the end of class or in asynchronous discussion threads. Prompts can be broad: “What was the most valuable concept or skill discussed in todays (this weeks’) class?” or specific: “What aspect of (a concept or process) did you understand the best? or where did you get confused?” These are sometimes referred to as ‘1-minute papers’. These can be done by student pairs and include brief discussions, or by individuals.

-

Provide practical examples after concept/theory learning and allow students to work with concepts/problems and demonstrate to themselves what they can do after the learning activity. Such practices can help students see what they are learning.

-

Promote interactions among students by providing chances for group discussions, team-working tasks, peer review process etc.

-

Create group learning activities (with clear roles and scaffolding) that can add a social aspect and support students who are challenged with materials.

-

Note this aspect includes group dynamics explicitly which has its own challenges but still worth it!

-

-

Begin a class period by asking students to recall and share knowledge gains from previous lectures. This allows students to acknowledge that they are learning (don’t choose obscure factoids but rather large focal concepts😊)

-

A recap from previous lectures related to the material you are going to teach gets students engaged right away just like the recap you might need for your favorite TV shows. Try to help students connect the material with old knowledge or daily life just as this suggestion did:-)

It is worth considering the ‘second tier’ of important factors that relate significantly to one or the other form of engagement as well. Some of the ideas presented above already hit these topics: such as, provide active learning opportunities interspersed in your course (for more ideas see: Don’t Throw the Baby out with the Bathwater…); and, when possible, give students ‘choice’ in:

-

activity

-

form of expression,

-

rules of engagement.

While “challenge” was identified as being negatively correlated with emotional engagement, other studies have suggested that high expectations are necessary for successful learning, thus working to support challenging topics through scaffolded group work, paired activities, or individual feedback and intervention where possible are good alternatives.

Unpacking individual student engagement makes it easier for educators to understand why great pedagogical ideas don’t always work as well as we expect. It helps us pinpoint what we can work with to get ideas across and create critical thought. We now have some understanding of why, on any given day, those implemented practices may leave us feeling satisfied, even elated, about what happened in our online or face-to-face classrooms – or alternatively frustrated and disheartened. Optimistically, ‘mode’ of teaching (online versus face-to-face) is NOT nearly as strong a correlate with engagement as other measured variables over which we have some control. There are many ways to continue to work with our own personal strengths and challenges as we strive to improve learning outcomes. As a final note, and an enticement to look for our for the next post in this series, individual student choices, behaviors, and motivations are further complicated by the ‘dynamic’ in the class among members. This is likely particularly true when one makes good evidence-base choices at the course level to facilitate long or short-term collaborative learning experiences. The plot thickens… But in the meantime…

Unpacking individual student engagement makes it easier for educators to understand why great pedagogical ideas don’t always work as well as we expect. It helps us pinpoint what we can work with to get ideas across and create critical thought. We now have some understanding of why, on any given day, those implemented practices may leave us feeling satisfied, even elated, about what happened in our online or face-to-face classrooms – or alternatively frustrated and disheartened. Optimistically, ‘mode’ of teaching (online versus face-to-face) is NOT nearly as strong a correlate with engagement as other measured variables over which we have some control. There are many ways to continue to work with our own personal strengths and challenges as we strive to improve learning outcomes. As a final note, and an enticement to look for our for the next post in this series, individual student choices, behaviors, and motivations are further complicated by the ‘dynamic’ in the class among members. This is likely particularly true when one makes good evidence-base choices at the course level to facilitate long or short-term collaborative learning experiences. The plot thickens… But in the meantime…

Happy experimenting!

Manwaring, K. C., Larsen, R., Graham, C. R., Henrie, C. R., & Halverson, L. R. (2017). Investigating student engagement in blended learning settings using experience sampling and structural equation modeling. Internet and Higher Education, 35, 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.06.002