If you are teaching a topic, it is likely that you have a high level of preparedness, intuition, and ability that has been developed beyond the level of many of your learners. Unpacking a complex problem into logical steps, assessing what information is necessary to begin and move forward, and understanding what constitutes a ‘reasonable’ or ‘plausible’ answer may happen almost unconsciously!

Dreyfus and Dreyfus (2005) suggest that there are distinct steps, or stages from novice to expert. The highest level of skill – expert – is marked by ‘intuition’ which is built through time, trouble shooting, struggle, metacognition, and reflection

‘expertise is based on the making of immediate, unreflective situational responses; intuitive judgment is the hallmark of expertise.’ (pg 779)

While some may disagree with the fine points of the Dreyfus and Dreyfus model, they do agree with the general process through which expertise is developed. At this high level of understanding, much of the early conscious decision making has been incorporated into unconscious processes that happen behind the scenes.

Thus, teaching this material to many novice learners requires a conscious ‘unpacking’ of the problems/material. The ability to unpack more complex problems may be one of the key features of the peer-educator ‘Super Power’. Being able to take apart the problem that is being shared via lecture, in real time, even if the Professor may have ‘intuited’ and thus not shared some of the sub-text, is incredibly helpful for ones own learning and the ability to share it with peers. This is not a skill that all learners have.

Lacking the ability to easily ‘unpack’ problems does not mean that one won’t learn the material, only that they are coming into the challenge with a different knowledge-base and skillset. Keeping a growth mindset is critical! The generic model shared here is a tool to help peer (and other) educators remember to make explicit the steps, to consider the assumptions about what knowledge is needed to move through the process to the solution, and how to facilitate the procedure through the problem using guided questions.

Lacking the ability to easily ‘unpack’ problems does not mean that one won’t learn the material, only that they are coming into the challenge with a different knowledge-base and skillset. Keeping a growth mindset is critical! The generic model shared here is a tool to help peer (and other) educators remember to make explicit the steps, to consider the assumptions about what knowledge is needed to move through the process to the solution, and how to facilitate the procedure through the problem using guided questions.

Asking learners to use the model can also enhance their metacognition, make clear the gaps in their knowledge, and kick-start the self-evaluation (metacognitive) processes.

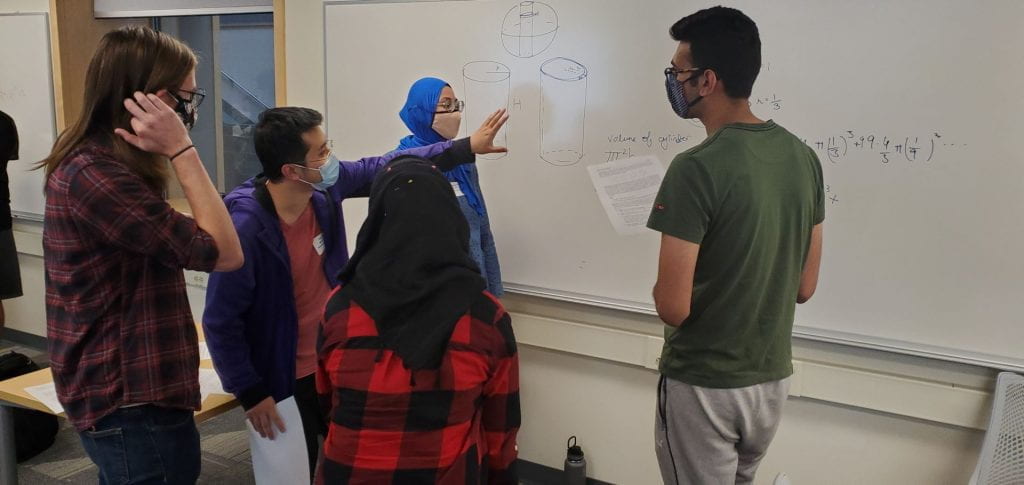

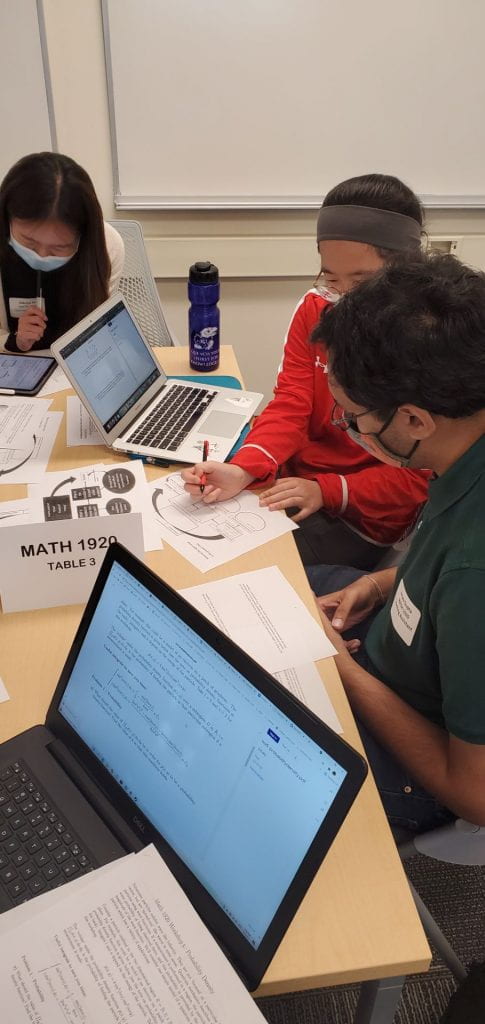

Once the educator has helped the learners breakdown the problem and students are working through the problem in small groups (3-5), the most powerful learning will happen when the facilitator acts as a ‘guide on the side’ by practicing listening, asking questions at appropriate cognitive levels, inviting the group to answer their own questions, and by using questioning strategies. This is the most challenging part of facilitating group work. At first students may resist the attempts the facilitator makes because there is cognitive work involved in answering guiding questions. If students are new to working in collaborative groups and are focused on solutions and getting there quickly, they may initially find it frustrating to receive a question in response to their questions. But once this is the expectation in a class, most students will begin to see the value, and become more comfortable with the uncertainty they experience with struggle. A few may never value this process. The learning literature confirms that the deeper, long-term learning that happens in collaborative group work is worth the effort.

Below is a checklist of tips that can help create a learning environment that will result in the best outcomes for small-group collaborative learning.

-

Tips for Guiding Small Group Discussion – ‘Just-in-time facilitating’

- Create an inclusive environment in which learners feel they can take risks

-

- When you approach a group that seems like they are facing a challenge say something like, “Oh yes! This problem, this is a hard one!” (or, “This is the hardest part of this, I think!”)

- Seeing you admit that it is challenging will allow them to feel better about the struggle and take the risk of discussing it!

- When you approach a group that seems like they are facing a challenge say something like, “Oh yes! This problem, this is a hard one!” (or, “This is the hardest part of this, I think!”)

- Encourage ALL learners to participate

- Keep the discussion from being dominated by a subset of learners.

- Allow sufficient “wait-time” when learners or you ask questions. Try to be aware of who is quiet and give them time to prepare to contribute – without singling them out, you can ask, “Is there anyone else who can add to this part of the process?”

- Intentionally ask the group members to take turns leading parts of a problem or different problems. Explain that the role of the leader is to begin the problem, invite others, and watch that group members are actively listening and sharing equally.

- Listen actively and non-judgmentally, and encourage learners to do likewise.

- Build what learners say into the discussion

- When you are reiterating a question you have heard, try to weave the ideas of the group into the reiteration so they feel heard and valued.

- Help learners communicate and build on each other’s contributions

- Model being patient and encourage learners to do likewise.

- Build what learners say into the discussion.

- Use mainly open-ended questions or comments

- Keep the discussion from being dominated by a subset of learners.

-

- Start with, “How is this problem going?” Follow with, “Is everyone feeling good about it, or would some discussion help?”

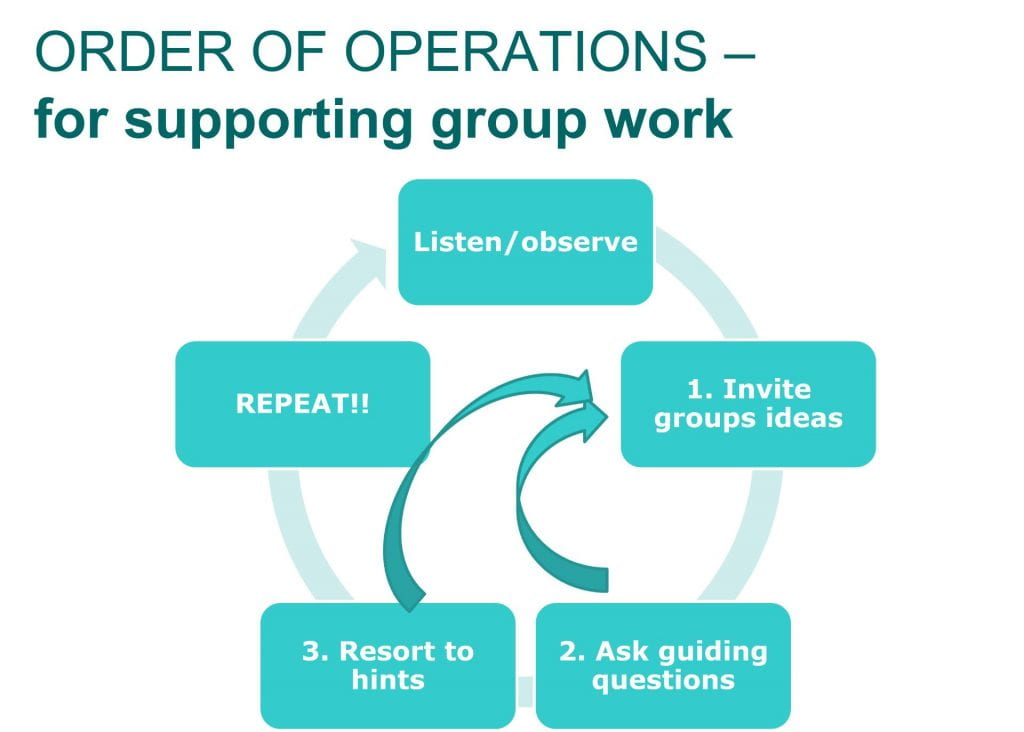

- Then use factual, or probing questions (remember the cycle: a) listen (maybe repeat the question back to all), b) invite the group to answer, c) choose a guiding question, and finally, d) give a hint (repeat).

- Encourage active listening

-

- Modeling this in your group (as above) and inviting the group members to try it when each of them share questions can help group communication be more equitable and bring everyone into the conversation.

- Foster dialogue amongst the learners and help them to see multiple points of view

-

- After someone makes a comment or shares an idea: Wait for the others to think for a few seconds, acknowledge and appreciate the answer, and then ask, “Does anyone want to add to that, or have a different idea?”

- Probe the learners’ understandings and foster higher-level thinking and discussion

-

- Using the probing questions at this point will help foster more process-oriented thinking – higher-order thinking.

- Help the learners digest what they are hearing

-

- In a short session like the one you are working in, a collected short paragraph reflection as the students leave could be really valuable to get the feedback, but also to let students convert experience into understanding through reflection.

Educators, even peer educators, need to deliberately articulate the assumptions, prior knowledge, and process steps that can help new learners into and through a complex problem. Helping novice learners unpack the problem and guiding from the side with careful listening and probing questions, while the learners share the struggle of trouble-shooting, will result in the best learning outcomes. It is this process, facilitated with a growth mindset, that helps create equity and inclusion and starts all learners along a path to self-assessment and, with time, expertise!!