Being able to apply information that is learned in one context to solve problems in another context, is known as ‘transfer’. Many would argue that being able to transfer concepts and knowledge to a new context is the true test of learning. We agree!

“A central and enduring goal of education is to provide learning experiences that are useful beyond the specific conditions of initial learning.”

(Lobato, 2006, in Nokes-Malach and Richey 2015)

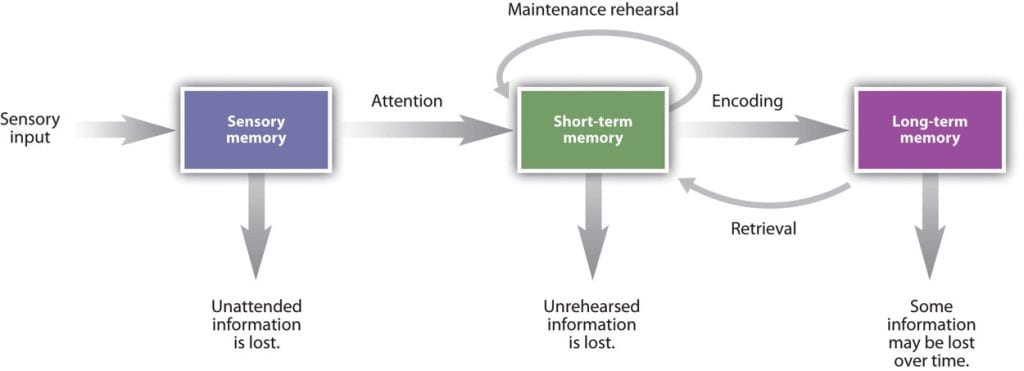

It turns out that researchers have been arguing over, and studying, both content and context in which learning transfer fails or succeeds since the very early 1900s. Nokes-Malach and Richey (2015), summarize the arguments, research, and outcomes in this complex literature. For our purpose of sharing practices that can make transfer more likely, we will focus on the outcomes. To illustrate just a bit about the complexity of this topic, transfer of knowledge can be: ‘near’ (executing learned procedures), ‘intermediate’ (adapting learned procedures), and ‘far’ transfer (relating concepts to each other and to new problems with different features).

Examples will be discipline specific. Here are examples of where transfer of knowledge is required in a civil engineering design course:

Basic Knowledge: Structural Analysis (Beam). Using the principles of statics and mechanics of materials, students learn to determine the shear force, bending moment, and deflection along the length of the beam.

Near transfer: Structural Analysis (Frame). Students are asked to analyze a structural frame, such as a door frame. The frame consists of interconnected beams and columns, subjected to various loads and boundary conditions.

-

In the frame analysis, there is a more complex structural system with multiple members connected at joints. This requires additional considerations and analysis techniques (frame stability, joint behavior, and load distribution among members).

Intermediate transfer: Truss Analysis. This problem involves the analysis of a truss structure. The truss consists of interconnected members subjected to external loads.

-

The new approach must be adapted to account for the unique characteristics of truss structures (i.e. axial forces in the members).

Far transfer: Foundation Design: This example involves the design of a structural foundation. The structure has specific requirements for load-bearing capacity, settlement, and stability

-

Designing a foundation system that interacts with the underlying soil and supports the entire structure involves applying principles from different areas of civil engineering, such as geotechnical engineering and foundation design, which may not have been directly addressed in the analysis of a beam.

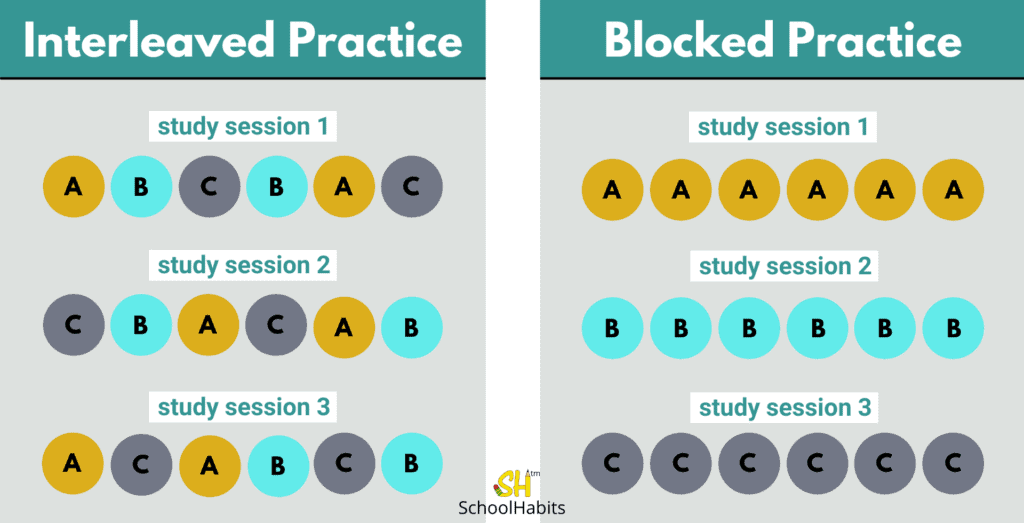

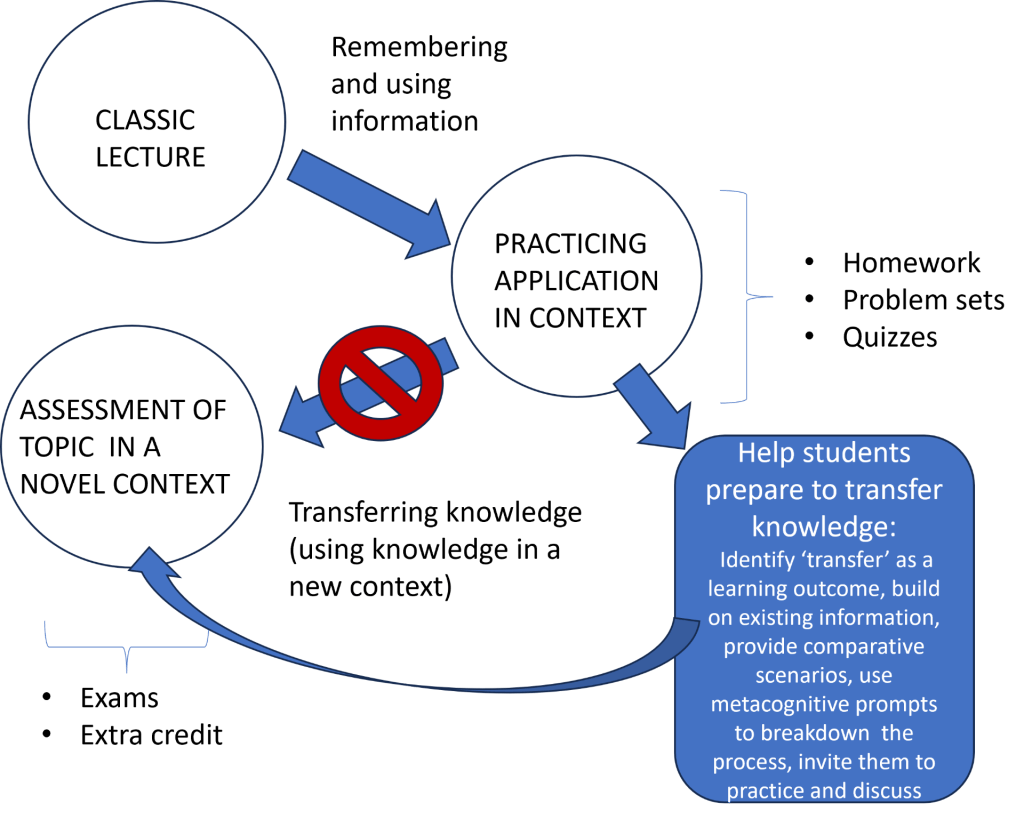

These levels of transfer require different skills and likely help explain the variety of learning outcomes in the transfer literature. Applying, adapting, comparing and contrasting, and evaluating are (more or less) progressively more challenging cognitive tasks (think ‘Blooms taxonomy’, Agarwal, 2018). These different levels can be promoted using different learning strategies.

If transfer of knowledge is an expectation and it requires critical thinking skills, this should be transparent in the learning objectives for the course and/or assignment. Rather than teaching or practicing these skills, it may be that students are expected to already have these skills. Some likely do; others do not and need structured practice. This is a question of equity. Because students are transitioning to college courses from a variety of educational experiences, not all have been challenged to critically think and transfer complicated knowledge to a new context. This does not mean they are unable to learn how. If we make assumptions about students’ critical thinking skills, we perpetuate an inequitable situation in our classrooms and institutions.

Higher level critical thinking skills needed for information transfer include the ability to analyze, compare contrast, link concepts, and evaluate approaches. These skills can be practiced and scaffolded so that students who have a grasp on content in the context it was taught can know how to use that information in a new context.

- Identifying ‘knowledge transfer’ as an expected learning outcome.

- Scaffolding complex problems by helping students build on the basic information using metacognitive questions and reflection.

- Comparing and contrasting the simple questions with more complex questions.

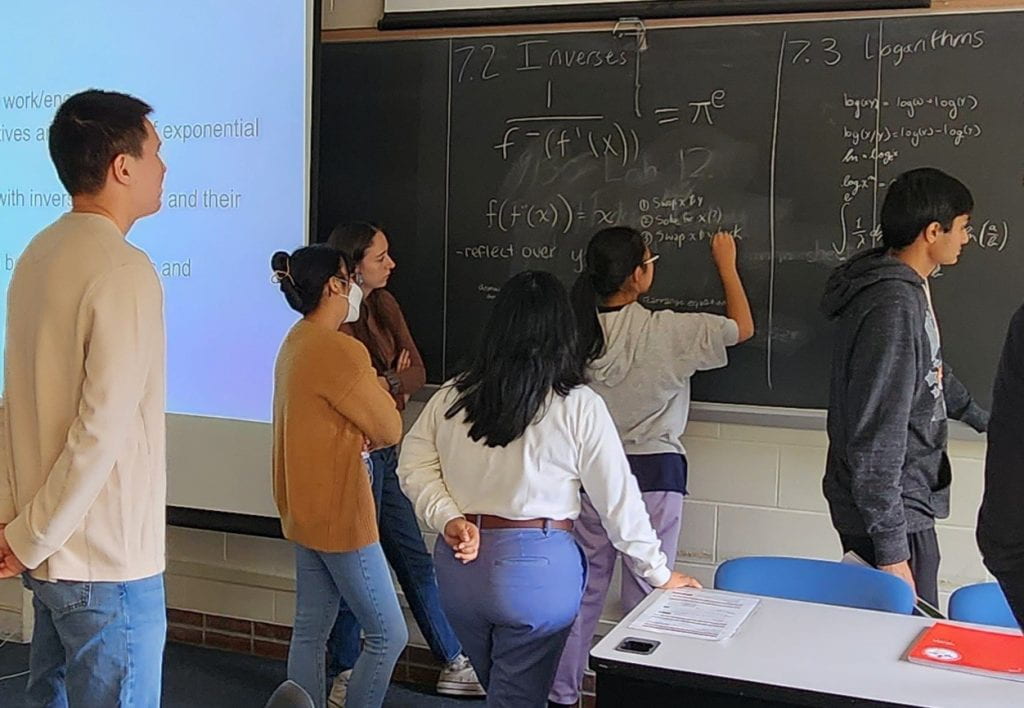

- Provide relevant real-world problems for students to practice and collaborate on.

- One key here is inviting students – in groups – to practice and discuss a progression of problems from one context to another.

This is an easy way to help our students be more successful in their learning. Happy teaching and learning. Happy transferring!!

Again, read your syllabus and your assignments. Look for purpose, tasks, and criteria. Read for unfamiliar terms or phrases. Remember, the language and expectations may not be familiar to you for a host of reasons, for which you are not to blame! After you have paid careful attention to the materials provided, go to office hours, ask in class when opportunities arise, or reach out after class to the instructor, TAs, or other members of the teaching staff.

Again, read your syllabus and your assignments. Look for purpose, tasks, and criteria. Read for unfamiliar terms or phrases. Remember, the language and expectations may not be familiar to you for a host of reasons, for which you are not to blame! After you have paid careful attention to the materials provided, go to office hours, ask in class when opportunities arise, or reach out after class to the instructor, TAs, or other members of the teaching staff.